The short version

Have you ever wondered why neurons are like snowflakes? No two alike, even if they're the same type. In our latest preprint, we think we have (at least part of) the answer: it promotes robust learning.

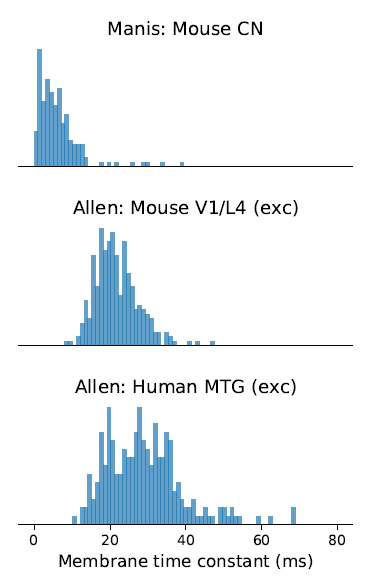

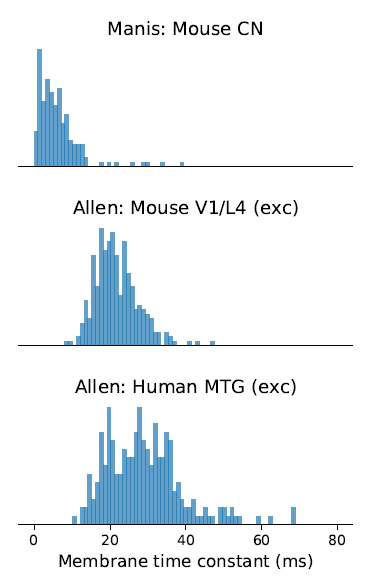

One of the striking things about the brain is how much diversity there is at so many levels, e.g. the distribution of membrane time constants. Check these out from the Allen Institute and Paul Manis - there's a wide range of values for single cell types, a bit like a log normal distribution.

But, most models of networks of neurons that can carry out complex information processing tasks tend to use the same parameters for all neurons of the same type, with typically only connectivity being different for each neuron.

We guessed that networks of neurons with a wide range of time constants would be better at tasks where information is present at multiple time scales, such as auditory tasks like recognising speech.

Since we were interested in temporal dynamics and comparing to biology, we used spiking neural networks trained using surrogate gradient descent, adapted to learn time constants as well as weights.

We found no improvement for N-MNIST which has little to no useful temporal information in the stimuli, some improvement for DVS gestures which does have temporal info but can be solved well without using it, and a huge improvement for recognising spoken digits.

The distributions of time constants learned are consistent for a given task, for each run, and regardless of whether you initialise time constants randomly or at a fixed value. And, they look like the distributions you find in the brain.

And it's more robust. If you tune hyperparameters for sounds at a single speed, and then change the playback speed of stimuli, the heterogeneous networks can still learn the task but homogeneous ones start to fall down.

We also tested another training method, spiking FORCE (Nicola and Clopath 2017), and found the same robustness to hyperparameter mistuning. This figure shows the region where learning converges to a good solution in blue, axes are hyperparameters.

So this looks to be pretty general: heterogeneity improves learning of temporal tasks and gives robustness against hyperparameter mistuning. And it does so at no metabolic cost. The same performance with homogeneous networks requires 10x more neurons! So, surely the brain uses this?

This is also good for neuromorphic computing and ML: adding neuron level heterogeneity costs only O(n) time and memory, whereas adding more neurons and synapses costs O(n²).

That's it for the results, we hope that this spurs people to look further into the importance of heterogeneity, e.g. spatial or cell type heterogeneity, and whether it can be useful in ML too.

If you're interested in this area, there's a fascinating literature on heterogeneity, briefly reviewed in this paper, including similar work with a more neuromorphic angle from Sander Bohte and Tim Masquelier. There's a nice review in Gjorgjieva et al. (2016).

This work was only possible thanks to two incredible scientific developments. The first is new methods of training spiking neural networks from Friedemann Zenke and others. We had a workshop on this over the summer, videos available at the SNUFA 2020 playlist.

The second is the availability of incredible experimental datasets thanks to orgs like the Allen Institute, the NeuroElectro Database and individual labs like Paul Manis'. Thank you so much for your generosity!

Neural heterogeneity promotes robust learning

Abstract

Links

Related videos

-

Understanding the role of neural heterogeneity in learningTalk / 2021

Talk on neural heterogeneity by Nicolas Perez. -

Neural heterogeneity promotes robust learningTalk / 2021

Talk on neural heterogeneity by Dan Goodman.

Categories

The short version

One of the striking things about the brain is how much diversity there is at so many levels, e.g. the distribution of membrane time constants. Check these out from the Allen Institute and Paul Manis - there's a wide range of values for single cell types, a bit like a log normal distribution.

But, most models of networks of neurons that can carry out complex information processing tasks tend to use the same parameters for all neurons of the same type, with typically only connectivity being different for each neuron.

We guessed that networks of neurons with a wide range of time constants would be better at tasks where information is present at multiple time scales, such as auditory tasks like recognising speech.

Since we were interested in temporal dynamics and comparing to biology, we used spiking neural networks trained using surrogate gradient descent, adapted to learn time constants as well as weights.

We found no improvement for N-MNIST which has little to no useful temporal information in the stimuli, some improvement for DVS gestures which does have temporal info but can be solved well without using it, and a huge improvement for recognising spoken digits.

The distributions of time constants learned are consistent for a given task, for each run, and regardless of whether you initialise time constants randomly or at a fixed value. And, they look like the distributions you find in the brain.

And it's more robust. If you tune hyperparameters for sounds at a single speed, and then change the playback speed of stimuli, the heterogeneous networks can still learn the task but homogeneous ones start to fall down.

We also tested another training method, spiking FORCE (Nicola and Clopath 2017), and found the same robustness to hyperparameter mistuning. This figure shows the region where learning converges to a good solution in blue, axes are hyperparameters.

So this looks to be pretty general: heterogeneity improves learning of temporal tasks and gives robustness against hyperparameter mistuning. And it does so at no metabolic cost. The same performance with homogeneous networks requires 10x more neurons! So, surely the brain uses this?

This is also good for neuromorphic computing and ML: adding neuron level heterogeneity costs only O(n) time and memory, whereas adding more neurons and synapses costs O(n²).

That's it for the results, we hope that this spurs people to look further into the importance of heterogeneity, e.g. spatial or cell type heterogeneity, and whether it can be useful in ML too.

If you're interested in this area, there's a fascinating literature on heterogeneity, briefly reviewed in this paper, including similar work with a more neuromorphic angle from Sander Bohte and Tim Masquelier. There's a nice review in Gjorgjieva et al. (2016).

This work was only possible thanks to two incredible scientific developments. The first is new methods of training spiking neural networks from Friedemann Zenke and others. We had a workshop on this over the summer, videos available at the SNUFA 2020 playlist.

The second is the availability of incredible experimental datasets thanks to orgs like the Allen Institute, the NeuroElectro Database and individual labs like Paul Manis'. Thank you so much for your generosity!